I. Introduction: The Enduring Allure of Chinese Incense and Hexiangzhu

Incense, universally known in Chinese as xiang (香), represents far more than a mere aromatic substance within Chinese culture; it embodies a profound and multifaceted history that spans millennia. Its origins trace back to Neolithic times, gaining significant prominence during the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.1 This broad category of aromatics transcended simple olfactory pleasure, finding diverse applications across sacred, profane, public, and private spheres of social life.1 The historical record reveals a fluid distinction in medieval China among substances categorized as drugs, spices, perfumes, and incenses, all serving purposes ranging from nourishing the body or spirit to attracting divinities or lovers.1 This pervasive integration suggests that incense in China was inherently holistic, intertwined deeply with health, spirituality, and social standing. The widespread adoption of incense, and subsequently

Hexiangzhu, can be attributed to this multi-functional integration, extending beyond its aromatic qualities alone.

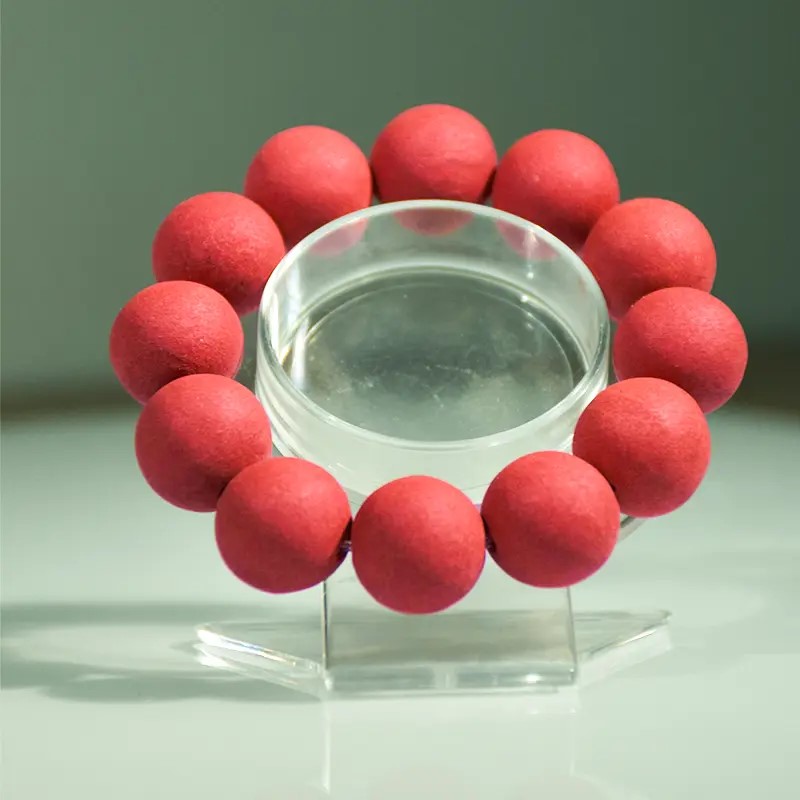

At the pinnacle of this rich aromatic tradition stands Hexiangzhu (合香珠), or compounded incense beads. These distinctive creations are meticulously hand-crafted ornaments, fashioned from a precise blend of natural spices and medicinal herbs, prepared according to ancient, time-honored techniques.4 A defining characteristic of

Hexiangzhu is their ability to emit an elegant and enduring fragrance, setting them apart from simpler, single-ingredient incenses.4 Their utility extends beyond their captivating scent;

Hexiangzhu serve a dual function as aesthetic adornments, often worn on the wrist or neck, and as refined decorative elements for indoor spaces.4 Furthermore, they are recognized for their calming and health-promoting properties, embodying the very essence of Eastern incense culture.4

It is crucial to clarify that “Hexiangzhu” (合香珠) refers exclusively to these compounded incense beads. This term should not be conflated with “Zhu Xi” (朱熹), the eminent Neo-Confucian philosopher of the Southern Song dynasty, whose profound influence shaped Chinese intellectual foundations for centuries.6 Nor should it be confused with “xiangzhu” (香烛), which denotes joss sticks and candles, common religious offerings.9 The focus of this report is solely on the intricate world of compounded incense beads.

The historical trajectory of Chinese incense demonstrates a clear evolution from its early utilitarian applications—such as combating dampness, purifying air, and facilitating religious sacrifices 10—to becoming a sophisticated art form. By the Han dynasty, increased trade along the Silk Road introduced new foreign fragrances, elevating incense beyond local “poor man’s incense”.1 This trajectory continued through the Song dynasty, where incense became a popular cultural pastime for the nobility, leading to the construction of dedicated incense rooms.1 The eventual emergence of

xiangdao (香道), meaning “the way of the scent,” as a refined art form comparable to tea ceremonies and calligraphy 1, marks a profound cultural transformation.

Hexiangzhu, as a “compounded” product, directly manifests this evolution. The inherent complexity in its ingredients and preparation reflects the sophisticated pursuit of xiangdao, elevating incense use from simple burning to an intricate sensory, intellectual, and artistic experience. The compounded nature allows for greater artistic expression and the creation of highly nuanced and layered aromatic profiles.

This article will delve into the intricacies of Hexiangzhu by drawing extensively from Xiang Cheng (香乘), a pivotal Ming Dynasty compendium on incense culture.3 Authored by Zhou Jiazhou (also known as Zhou Wei-Zhou or Zhou Jiaxuan) 14,

Xiang Cheng stands as an invaluable historical and practical guide, widely regarded as the “bible” for traditional Chinese incense.14

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Chinese Incense Culture and Hexiangzhu

| Dynasty/Period | Approximate Dates | Key Developments in Incense Culture | Relevance to Hexiangzhu / Hexiang | Relevant Source(s) |

| Neolithic | – | Early use of xiang (fragrance) | Incense used from ancient times | 1 |

| Xia, Shang, Zhou | – | Greater prominence of xiang | Foundation for later developments | 1 |

| Spring & Autumn | c. 770 – c. 481 BCE | Emergence of incense burning for rituals and combating dampness | Early utilitarian uses of aromatics | 10 |

| Han | 206 BCE – 220 CE | Increased trade, foreign fragrances (sandalwood, camphor, frankincense) imported. Hill censers (boshanlu) popular. Buddhism introduced, intensifying religious connotation. | Introduction of diverse ingredients, early forms of compounded pastes | 1 |

| Tang | 618–907 CE | Peak of incense culture, spread to Japan. Emergence of premixed Hexiang products (powders, pellets, ointments). Incense time-keeping devices. | First appearance of complex, premixed Hexiang products. | 1 |

| Song | 960–1279 CE | Incense transitions from religious to secular realm. Indispensable for literati life. Xiangdao (Way of Scent) develops as an art form. First compendiums on fragrances compiled. | Hexiang integral to refined literati practices, fostering sophisticated blending | 1 |

| Ming | 1368–1644 CE | Incense culture “demystified,” permeating all social aspects. Marker of social status. Xiang Cheng compiled. | Context for Xiang Cheng‘s compilation; Hexiangzhu as a refined product of this era | 3 |

| Qing | 1644–1912 CE | Xiang Cheng included in Siku Quanshu. | Recognition of Xiang Cheng‘s authoritative status | 5 |

| Republic of China & Modern | 1912 CE – Present | Gradual replacement by Western perfumes. Incense use largely confined to religious sacrifices. Concern over chemical fragrances. Efforts to reconstruct traditional recipes. | Decline of traditional Hexiangzhu use, but renewed interest in preservation | 5 |

II. Defining Hexiangzhu: Characteristics and the Concept of Hexiang

Hexiangzhu are precisely defined as traditional, hand-crafted ornaments.4 Their primary composition involves natural spices and medicinal herbs, meticulously blended according to ancient techniques.4 These beads are characterized by their elegant and long-lasting fragrance, which distinguishes them from simpler single-ingredient incenses.4 Beyond their aromatic appeal,

Hexiangzhu serve a dual purpose: they function as aesthetic adornments, wearable on the wrist or neck, and as refined indoor decorations.4 Crucially, they are also recognized for their calming and health benefits, embodying the essence of Eastern incense culture.4 This integrated approach means

Hexiangzhu addresses multiple layers of human needs—sensory pleasure, physical health, and spiritual tranquility. This multi-functionality is a key reason for their enduring appeal and deep cultural embedding in traditional Chinese life, making them valuable beyond their immediate aromatic output.

The term Hexiang (合香), meaning “blending of aromatics,” is foundational to understanding Hexiangzhu. This practice involves combining multiple aromatic ingredients to create a more complex and harmonious scent profile.18 Historically,

Hexiang emerged as a significant development in Chinese incense culture. While ancient practices involved burning single herbs or simple combinations, the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) marked a turning point.19 With increased cross-border trade and the importation of exotic spices,

Hexiang evolved into sophisticated premixed products, including fragrant powders, pellets, and ointments.19 This innovation allowed for greater complexity and consistency in fragrance.

Archaeological evidence supports the early practice of Hexiang, with a mixture of agarwood and frankincense found in a 9th-century silver container at Famen Royal Temple, providing direct evidence of Hexiang making in ancient China.19 This also reflects the contemporary knowledge and appreciation of exotic incense.23 The historical progression from single-flavor incense to

Hexiang and the subsequent emergence of premixed products during the Tang Dynasty signifies an increasing sophistication in Chinese incense culture.5 The description of blending for “harmony” and achieving a “higher principle” 21 suggests an advanced understanding of perfumery, moving beyond simple mixing to a deliberate artistic and scientific endeavor.

Hexiangzhu embodies this peak of sophistication. Its “compounded” nature is not merely about combining ingredients but about achieving a synergistic effect where the overall aromatic experience is richer and more profound than the sum of its individual components. This pursuit of a complex, unified scent distinguishes Hexiangzhu from earlier, simpler forms of incense.

III. Xiang Cheng: A Ming Dynasty Masterpiece on Incense Culture

Xiang Cheng (香乘), often translated as “History of Incense” or “Treatise on Perfumes,” is a monumental work authored by Zhou Jiazhou (周嘉胄) during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE).5 Zhou Jiazhou, recognized as a renowned intellectual of his time, dedicated over two decades to its meticulous research and compilation, with the first manuscript completed around 1618 CE.14 The Ming Dynasty was a period characterized by the “demystification” of incense culture, allowing it to permeate almost all aspects of Chinese social life. This meant incense use extended beyond religious or scholarly confines to open public spaces, becoming a marker of social status for the elite.3 This widespread use and the continuous development of the fragrant medicine trade created a fertile ground for the compilation of comprehensive texts like

Xiang Cheng.5

Xiang Cheng is widely regarded as the “bible” for Chinese incense and incense crafts.14 Its comprehensive nature encompasses detailed information on numerous incense ingredients, their various uses, a multitude of recipes and blends, and a rich collection of Chinese historical anecdotes and stories related to incense.14 It includes ancient recipes from imperial palaces, Buddhist temples, and various private incense houses, reflecting the diverse applications and traditions of incense.14 The compilation of

Xiang Cheng in the Ming Dynasty, following centuries of significant incense development across the Han, Tang, and Song periods, suggests it was a monumental effort to consolidate and systematize previously dispersed knowledge. Its designation as a “comprehensive guide” 14 and its prestigious inclusion in the

Siku Quanshu indicate a recognized need to preserve and formalize this rich cultural heritage amidst its widespread adoption.

The authoritative status of Xiang Cheng is further underscored by its inclusion in the Imperial encyclopedia Siku Quanshu (《四库全书》) in the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty.5 Of the seven commissioned copies for this encyclopedia, four survive today, along with another edited version preserved in Japan’s Waseda University Library.14 This demonstrates its enduring scholarly and cultural value across East Asia. Modern incense practitioners and scholars continue to study

Xiang Cheng, with its classic recipes forming the basis for contemporary products and research.14 For instance, the ‘芙蕖Lotus’ scent for

xiangnang (sachets) is directly inspired by an ancient prescription found within Xiang Cheng, featuring ingredients like clove, sandalwood, nard, tonka, peony, and fennel.24 The book also contains medical incense recipes, such as one by Zhou Jiazhou himself for “Recovery from Weakness and Disease,” emphasizing heating over burning for therapeutic effects.15 The book’s content demonstrates a unique blend of practical recipes, historical anecdotes, and its overall structure as a scholarly compendium. This multi-faceted nature suggests that incense culture was not simply a craft but an intellectual pursuit, requiring both empirical knowledge of ingredients and their properties, as well as a deep appreciation for the cultural and historical dimensions of fragrance.

Xiang Cheng validates the creation of Hexiangzhu as a product of both scientific understanding, particularly of medicinal herbs and their therapeutic properties, and refined artistic sensibility in blending for harmonious and specific effects. It elevates the practice of making Hexiangzhu from a simple craft to a scholarly art form, reflecting the literati’s pursuit of holistic cultivation where intellectual rigor and aesthetic appreciation converge.

IV. The Craft of Hexiangzhu: Ingredients and Traditional Preparation Methods

The creation of Hexiangzhu is an intricate process, relying on a diverse palette of natural ingredients and time-honored techniques that reflect centuries of accumulated knowledge.

Diverse Categories of Ingredients

Traditional Hexiangzhu are crafted from an array of natural dry ingredients, broadly categorized into four main types 14:

- Woods: Essential to the base and character of many blends, these include sandalwood (檀香), agarwood (沈香, aloeswood), Chinese cedar (翠柏), and nanmu (楠木).1 Agarwood and sandalwood, known for their deep and complex aromas, often form the foundation of pure incense powders.25

- Flowers: Contributing delicate and often ethereal notes, common floral ingredients include rose and osmanthus.14 The ‘芙蕖Lotus’ scent, directly inspired by a prescription in

Xiang Cheng, notably incorporates peony.24

- Herbs: A wide variety of herbs are utilized, many of which overlap significantly with the Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) pharmacopoeia. Examples include rhubarb (大黃), citronella, lily magnolia, and mugwort.1 Other specific herbs found in medical incense recipes, such as those for the “Free and Easy Wanderer Incense” (Xiao Yao San), include bupleurum root, dong quai root, atractylodes root, white peony root, licorice root, ginger, and peppermint leaves.26

- Resins: These provide depth, fixative qualities, and often a spiritual dimension to the fragrance. Common resins include frankincense (乳香), benzoin (安息香), myrrh, and styrax.1

Minor categories also include dried animal parts, such as musk and shells, and dried fruit parts, like citrus peel.14 The strong correlation between incense ingredients and TCM materia medica indicates that

Hexiangzhu formulation is not arbitrary but follows principles akin to compounding traditional Chinese herbal remedies. This suggests that Hexiangzhu are not merely perfumes but function as “aromatherapy medicine.” Their creation involves a deep understanding of materia medica, the energetic properties of various herbs, and the art of synergistic blending, much like a traditional Chinese physician would formulate a complex decoction.

Traditional Preparation Techniques

The creation of Hexiangzhu involves meticulous processes to transform these raw materials into a refined product:

- Powderization and Grinding: Ingredients are typically reduced to a fine powder using blenders or traditional tools such as stone mills or wooden mallets, followed by sifting to achieve a uniform, very fine consistency.25 Specific care is paramount for delicate aromatics like sandalwood, which should be air-dried slowly and ground at low temperatures to preserve its volatile aromatic oils, avoiding heat-generating power saws or high-speed grinders.25

- Mixing and Blending: The powdered ingredients are then mixed evenly. Traditional Chinese incense blends often follow a structured approach similar to TCM formulas, incorporating “sovereign,” “minister,” “assistant,” and “courier” ingredients, each serving a specific role in the overall composition.14 A typical recipe structure might involve approximate proportions such as 60% base powder, 10% secondary, 5% enhancing or fixative agents, and 25% binder.14

- Binding: A crucial step for forming the beads or sticks is the addition of a binder. Nanmu powder (抹香, Machilus thunbergii), a common wood-based binder, becomes adhesive when wet and minimally affects the final fragrance, making it ideal for preserving the intended aromatic profile.1 Historically, Elm bark powder (

Yu bark powder) was also utilized.14 The detailed discussion contrasting

Nanmu powder with Elm bark powder, including concerns about “fake” powders and quality deterioration, highlights the critical role of binders in incense integrity and the challenges of maintaining traditional quality standards.

- Forming: The mixed powders, moistened with decoctions or water, are kneaded into a dough-like consistency.26 This dough is then gently rolled into thin sticks, pressed into cones, or sculpted into various shapes like beads.1 For

Hexiangzhu, this specifically involves shaping the paste into small, often spherical, forms.

- Drying and Aging: Once formed, incense products are packed tightly and dried, ideally allowing for free airflow, a process that can take several days.26 Some medical incenses, such as the “Recovery from Weakness and Disease” formula from

Xiang Cheng, require an extensive aging process. This can involve burial in the ground for a number of weeks to fully mature their aroma and therapeutic efficacy.15 The emphasis on “handmade” processes 4 and specific, low-temperature grinding and careful drying methods 25 underscores the high value placed on artisanal skill and meticulous execution. The authentic quality and efficacy of

Hexiangzhu thus depend heavily on both the purity of raw materials and strict adherence to traditional, often labor-intensive, preparation methods. This implies that truly authentic Hexiangzhu are rare and valuable, representing a heritage of meticulous craftsmanship and material discernment that goes far beyond simple industrial production.

Heating vs. Burning

A significant distinction in traditional Chinese incense use, particularly for medical applications or subtle aromatic release, lies in the method of release: heating versus burning. Many Hexiang products, including certain medical incense pellets and likely Hexiangzhu, are designed to be gently warmed rather than ignited.15 This method releases a gentler, more nuanced aroma and is essential for preserving the delicate therapeutic properties of the herbs, allowing the user to “smell the aroma constantly” for recovery without further intervention.15 This contrasts with direct burning methods commonly used for joss sticks or cones, which produce more smoke and a more intense, but potentially less nuanced, fragrance.25 The specific “heating, not burning” method further supports the preservation of delicate medicinal compounds, emphasizing efficacy over mere smoke production.

Table 2: Key Ingredients and Their Traditional Roles in Hexiangzhu

| Category | Specific Ingredient (English Name) | Pinyin/Chinese Name | Traditional Role/Properties | Relevant Source(s) |

| Woods | Sandalwood | 檀香 (tánxiāng) | Base, aromatic, calming | 1 |

| Agarwood (Aloeswood) | 沈香 (chénxiāng) | Base, sovereign, highly prized aromatic | 1 | |

| Chinese Cedar | 翠柏 (cuìbǎi) | Aromatic wood | 1 | |

| Nanmu Powder | 楠木粉 (nánmùfěn) | Binder, adhesive when wet | 1 | |

| Resins | Frankincense | 乳香 (rǔxiāng) | Aromatic, spiritual, therapeutic | 1 |

| Benzoin | 安息香 (ānxīxiāng) | Aromatic, fixative | 1 | |

| Myrrh | 没药 (mòyào) | Aromatic, therapeutic | 14 | |

| Herbs | Bupleurum Root | 柴胡 (cháihú) | Therapeutic (TCM) | 26 |

| Dong Quai Root | 当归 (dāngguī) | Therapeutic (TCM) | 26 | |

| Licorice Root | 甘草 (gāncǎo) | Therapeutic (TCM), harmonizer | 26 | |

| Camphor | 樟脑 (zhāngnǎo) | Aromatic, therapeutic (dispels evil vapors) | 1 | |

| Clove | 丁香 (dīngxiāng) | Aromatic, therapeutic, courier | 1 | |

| Fennel | 大回香 (dàhuíxiāng) | Aromatic, therapeutic | 1 | |

| Flowers | Peony | 白芍 (báisháo) | Aromatic, therapeutic (TCM), used in ‘Lotus’ scent | 24 |

| Osmanthus | 桂花 (guìhuā) | Aromatic | 14 | |

| Other | Musk | 麝香 (shèxiāng) | Animal product, fixative, highly aromatic | 3 |

| Zhu Sha (Cinnabar) | 朱砂 (zhūshā) | Mineral, traditional ingredient (note: toxicity concerns for modern use) | 27 |

V. Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions of Hexiangzhu

The cultural significance of Hexiangzhu extends far beyond its physical form and aromatic output, deeply embedding itself within the fabric of Chinese society, spirituality, and daily life.

Daily Life and Aesthetic Adornment

By the Ming Dynasty, incense culture had undergone a process of “demystification,” allowing it to permeate almost all aspects of Chinese social life.3 No longer confined to religious rites or scholarly pursuits, incense became a prominent marker of social status for the elite.3

Hexiangzhu, as wearable ornaments or subtle indoor decorations 4, exemplify this integration. They provided a constant, subtle fragrance that enhanced personal spaces and garments, reflecting a sophisticated lifestyle where sensory experiences were highly valued and refined.3 The very act of carrying or displaying these beads indicated a cultivated taste and an appreciation for the subtle art of fragrance.

Religious and Spiritual Practices

Incense has historically served as a sacred bridge between the earthly and the divine throughout Chinese civilization.11 It was extensively employed in religious ceremonies, ancestor veneration, and both Buddhist and Daoist rituals.1 The burning or heating of incense was believed to purify the atmosphere, carry prayers to the heavens, and facilitate communication with higher beings, ultimately leading to greater wisdom and virtue.1 The rising smoke was often perceived as a “material representation through an ephemeral expression of the godly realm,” rendering the spiritual world accessible to human experience.20 The introduction of Buddhism to China, beginning in the Han Dynasty, significantly intensified incense’s religious connotation, with sutras describing “pure lands of incense” and its integral role in meditation.12 The consistent association of incense with “purification”—purifying temple atmospheres 3, cleansing body and mind 11, and even dispelling “evil vapors” in a medical context 1—reveals a deeply ingrained cultural belief system where fragrance is inherently cleansing, both physically and spiritually.

Hexiangzhu‘s advertised “calming and health benefits” 4 are not merely a convenient side effect but a direct extension of this profound cultural belief in the purifying and harmonizing power of aromatics. Its integration into daily life, even as a simple ornament, implicitly carries this purifying function, contributing to a holistic sense of well-being and harmony in one’s environment and inner self.

Traditional Chinese Medicine and Therapeutic Uses

As previously noted, Hexiangzhu shares ingredients and preparation techniques with Traditional Chinese Medicine.1 Incense was recognized by ancient doctors for its therapeutic effects, extending beyond mere aromatherapy.12 Specific examples include camphor, which was recommended for curing “evil vapors in heart and belly” and aiding eye troubles.1 The “Recovery from Weakness and Disease” recipe from

Xiang Cheng highlights its direct application in patient recovery, where constant inhalation of the aroma was prescribed for resolving weakness and disease without further intervention.15 This underscores its role in promoting comprehensive physical and psychological well-being.12

Incense as an Art Form (Xiangdao)

The sophisticated art of incense burning, known as xiangdao (香道, “the way of the scent”), developed in China, achieving a status comparable to tea ceremonies and calligraphy.1 This practice involved specific paraphernalia and utensils, often used to create intricate ideograms with incense powder.1

Xiangdao was believed to nourish the spirit and mind, serving as an aid and companion to reading, contemplation, and meditation for the literati.1

Hexiangzhu, with their complex blends and refined presentation, fit seamlessly into this artistic and contemplative tradition. The shift towards secular incense use and the emergence of xiangdao among scholar-officials during the Song Dynasty occurred concurrently with a “revivified Confucianism”.3 Key Neo-Confucian figures like Zhu Xi, though distinct from

Hexiangzhu, emphasized practices like “investigation of things” (格物) and “reverent concentration” (敬).6

Hexiangzhu, as a product of hexiang and an integral component of xiangdao, reflects the Neo-Confucian pursuit of self-cultivation and inner harmony. The meticulous blending, the nuanced appreciation of subtle fragrances, and the contemplative nature of xiangdao align perfectly with the Neo-Confucian emphasis on rigorous intellectual inquiry and mindful reflection. This positions Hexiangzhu as a tangible tool for intellectual and spiritual refinement within the literati tradition, demonstrating how external sensory engagement can facilitate the cultivation of the inner self.

Time-keeping

A unique secular application of incense, introduced with Buddhism, was its use as a time-keeping device.1 Calibrated incense sticks and clocks were first employed in Buddhist monasteries for vigils and subsequently spread into secular society for daily time measurement.1 This practical innovation further integrated incense into the daily rhythms of Chinese life, showcasing its versatile utility beyond its primary aromatic functions.

VI. Conclusion: Preserving the Legacy of Hexiangzhu

Hexiangzhu stands as a profound testament to the sophisticated and multifaceted incense culture of ancient China. From its origins in the broader practice of hexiang during the Tang Dynasty to its peak as a refined art form and therapeutic aid, these compounded incense beads embody a rich heritage of aesthetic, spiritual, and medicinal knowledge.4 The invaluable text

Xiang Cheng by Zhou Jiazhou serves as a cornerstone for understanding this legacy, meticulously documenting ingredients, recipes, and the intricate cultural context that elevated incense to an indispensable part of Chinese life.5

In modern times, traditional incense culture has largely been supplanted by Western perfumes, with its use primarily confined to religious ceremonies.5 A significant concern arises from the diminishing appreciation for the importance of natural fragrance quality, leading to the proliferation of inferior or chemical fragrances that may even pose harm.5 This decline indicates a severe risk of losing not just the physical products like

Hexiangzhu, but also the intricate knowledge, the artisanal craftsmanship, and the holistic philosophical underpinnings embedded within their creation and use. In this context, Xiang Cheng‘s role becomes even more critical as a primary repository of this endangered, yet invaluable, cultural and technical knowledge.

Reconstructing ancient recipes, such as those found in Xiang Cheng, presents significant challenges. These difficulties stem from changes in herb names over time, the rarity and expense of original ingredients, or safety concerns associated with historical components.15 Despite these obstacles, active efforts to reconstruct and revitalize these traditional practices are ongoing. These endeavors are driven by a recognition of the profound cultural, historical, and therapeutic value of

Hexiangzhu and the invaluable knowledge preserved in texts like Xiang Cheng.14

The enduring relevance of ancient wisdom for modern well-being is evident in the discernible and active effort to “reconstruct a number of recipes using the original herbs and processes”.15 The continued interest in

Hexiangzhu‘s “calming and health benefits” 4 suggests a contemporary appreciation for traditional, natural approaches to wellness and mindfulness, offering an alternative to purely synthetic solutions. This indicates a strong potential for revival, where

Hexiangzhu can offer a meaningful counter-narrative to modern, often synthetic, fragrances. Preserving the intricate art of Hexiangzhu and the timeless wisdom encapsulated in Xiang Cheng is crucial for maintaining a vital connection to China’s rich cultural past. Moreover, it offers a pathway to holistic well-being and mindful living in the contemporary world, providing a profound return to the “soul” of traditional incense culture.5