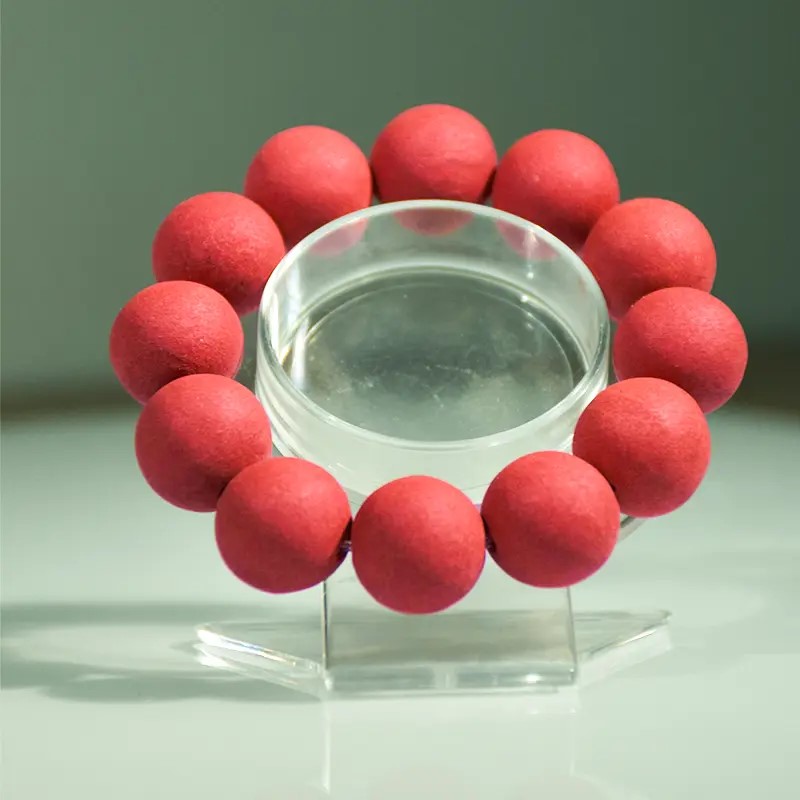

The captivating world of Hexiangzhu) (Incense beads) – beads meticulously crafted from precious incense powders and binders – holds a subtle yet crucial secret to authenticity and function etched onto their very surface: micropores. These tiny apertures, often described as “smiling” due to their delicate appearance, are far from mere aesthetic quirks. They are fundamental structural features arising from the unique material science and artisanal processes behind authentic Hexiangzhu), serving as vital markers for distinguishing genuine treasures from counterfeits and playing a key role in the bead’s olfactory performance. Understanding why these pores exist requires delving into the composition, crafting methods, and inherent physics of these aromatic jewels.

The Genesis of Gaseous Escape: Material Composition and Volatile Release

The primary origin of surface micropores lies in the very nature of the materials used and the processes involved in forming the bead:

Volatile Components & Trapped Gases: Genuine Hexiangzhu) are composed of complex blends of:

Finely Ground Incense Materials: Sandalwood, agarwood, clove, cinnamon, borneol, ambergris, musk, resins (like benzoin or frankincense), herbs, and spices. These organic materials inherently contain volatile aromatic compounds (essential oils, resins) and microscopic pockets of air within their cellular structures.

Natural Binders: Traditionally, binders like plum meat paste (Mei Rou), honey, or fruit extracts (e.g., jujube paste) are used. These are viscous, water-based solutions containing dissolved solids and organic compounds. Modern variants might use plant gums or food-grade natural binders, but water remains a common solvent.

The Shaping Process & Gas Entrapment: During the critical phase of forming the bead – whether hand-rolled or pressed into molds – the mixture of powdered incense materials and wet binder is compacted. This process inevitably traps:

Air: Existing within the powder particles and between them.

Water Vapor: From the aqueous binder.

Volatile Aromatic Compounds: Released from the incense powders as they are worked and warmed by the artisan’s hands.

Drying/Curing Dynamics & Gas Migration: As the shaped bead begins to dry and cure, several interconnected phenomena occur:

Water Evaporation: The liquid water in the binder turns to vapor. This vapor, along with the trapped air and volatile aromatics, needs to escape the densifying matrix.

Binder Shrinkage: Natural binders contract significantly as they lose water. This shrinkage creates internal stresses and micro-fractures within the bead’s structure.

Gas Expansion: Trapped gases expand slightly as the bead warms (during handling or ambient drying).

Path of Least Resistance: These expanding gases and vapors seek escape routes. They migrate through the still-pliable matrix, coalescing and forcing their way along paths of weaker cohesion or following the natural channels between incense particles. The surface of the bead represents the final barrier and the most direct path to the atmosphere.

Pore Formation: As the gases/vapors reach the surface and vent into the air, they leave behind microscopic voids – the pores. The rate of drying is crucial:

Slow, Natural Drying (Traditional): Allows gases to escape more gradually, typically resulting in smaller, more numerous, and relatively ordered pores visible to the naked eye as a characteristic fine texture. Under magnification, the inherent slight irregularity in particle size and distribution within the hand-mixed blend becomes apparent, leading to pores that are subtly varied in size and shape, with a natural, slightly “disordered” arrangement.

Rapid/Artificial Drying: Can cause violent outgassing, potentially leading to larger, fewer, or more irregular surface blisters or cracks, or conversely, trap gases internally if the surface seals too quickly.

Traditional Chinese Compound Incense

Traditional Chinese Compound Incense

The Delicate Art of Chinese aroma incense

Incense beads, or Chinese aroma incense beads , are far more than simple ornaments. These meticulously crafted spheres, born from the fusion of powdered precious woods, resins, herbs, and binding agents, represent a unique intersection of ancient Chinese fragrance culture, artistry, and contemplative practice. beads

The Artisan’s Hand: Crafting Technique as a Pore Modulator

The role of the artisan is paramount in shaping the nature of these pores:

Material Preparation: The fineness and uniformity of the incense powder grind influence particle packing and the size of inter-particle spaces, which become potential gas channels. A very fine, uniform powder might lead to smaller, more uniform pores if perfectly mixed, but absolute uniformity is rare in traditional hand processing.

Binder Ratio & Mixing: The amount and viscosity of the binder directly affect workability and gas entrapment. Too little binder results in a crumbly mixture prone to large voids and cracking. Too much binder creates a dense, plastic mass that can trap gases more effectively and shrink dramatically, potentially forming pores but also risking larger internal flaws or surface deformities. Hand mixing, while thorough, inherently introduces minor inconsistencies in binder distribution and particle packing compared to industrial homogenization.

Hand-Rolling Technique: This traditional method involves constant pressure and friction from the artisan’s fingers. This action:

Gradually Compacts the mixture, squeezing out some air but also warming the mass slightly, releasing more volatiles.

Creates a Smoother, Denser Surface Layer: The outer surface experiences the most direct friction and pressure, becoming slightly more compacted and polished than the immediate subsurface. Gases escaping from just below this denser surface layer are the ones most likely to create the characteristic surface micropores as they breach the final barrier. The pressure and heat gradient during rolling contribute to the specific “orderly yet subtly irregular” pore signature under magnification.

Drying Protocol: Artisans carefully control drying conditions (humidity, temperature, airflow). Slow, shaded drying is preferred. This controlled pace allows gases to escape steadily without causing disruptive ruptures, favoring the formation of the desirable fine, clear pores. Rushing this process damages the bead’s integrity and pore structure.

The Telltale Sign: Micropores as Authenticity Guardians

This complex interplay of materials and craftsmanship results in specific pore characteristics that are incredibly difficult for counterfeiters to replicate convincingly, making them a primary forensic tool:

- Authentic Hexiangzhu):

- Macroscopic View (Naked Eye): Surface exhibits a clear “powdery” or “woody” texture, distinct from polished stone or plastic. This is the visual manifestation of countless ordered, clear, fine, and distinct micropores. The surface feels slightly textured, not glassy smooth. Crucially, there’s a natural “particulate” or “woody grain” feel – you can sense the finely ground natural materials.

- Microscopic View (Magnification): Reveals the truth of the artisanal process. Pores, while generally fine and clear, show natural variation in size and shape. Their arrangement, while appearing ordered to the naked eye, under magnification shows a subtle, inherent “disorder” or “organic randomness” – a hallmark of hand-mixing, hand-rolling, and the natural variation in raw materials. They look like pathways formed by escaping gases through a compacted powder, not drilled or molded. Pores may appear deeper, with visible particle edges.

- Counterfeit Hexiangzhu) (Often Molded Resin/Plastic or Poorly Made Composites):

- Macroscopic View: Surface is typically too smooth, glassy, or waxy, lacking the characteristic fine pore texture. It feels artificial, like plastic or varnished wood. There is no discernible “woody grain” particulate feel. Sometimes, counterfeiters attempt to fake texture by:

- Molding in “Grain”: Creating artificial wood-like lines or patterns that look superficial and painted-on, not integral to the material.

- Surface Abrasion: Scratching the surface to mimic texture, but these marks look like scratches, not natural pores, and lack depth and the particulate feel.

- Poor Quality Pressed Powder: May have a rough, crumbly surface with large, irregular holes or cracks, not the fine, distinct pores. Often lacks density.

- Microscopic View: Confirms the lack of authenticity:

- Complete Absence of Pores: Surface is unnaturally sealed and uniform (common in resin fakes).

- Artificial “Pores”: If present, may look drilled, punched, or molded – too uniform in size, shape, and perfect circularity, arranged in overly rigid patterns. Lack depth and the natural connection to the internal structure. Look like dimples on the surface, not openings into the material.

- Surface “Grain” Illusion: Molded lines appear as shallow grooves without the complex internal structure or particulate edges visible in genuine pores. Looks like a surface stamp, not an emergent feature.

- Macroscopic View: Surface is typically too smooth, glassy, or waxy, lacking the characteristic fine pore texture. It feels artificial, like plastic or varnished wood. There is no discernible “woody grain” particulate feel. Sometimes, counterfeiters attempt to fake texture by:

Beyond Authentication: The Functional Role of Micropores

While authentication is critical, the micropores are not merely forensic artifacts; they serve a vital functional purpose:

- Enhanced Fragrance Diffusion (“Breathing”): The pores act as microscopic conduits connecting the bead’s aromatic interior to the external environment. This facilitates:

- Continuous Slow Release: Volatile aromatic compounds deep within the bead can slowly migrate along internal pathways and eventually reach the surface pores, ensuring a sustained, long-lasting fragrance emission characteristic of high-quality Hexiangzhu). A completely sealed surface would trap the scent internally.

- Interaction with Environment: The pores allow the bead to subtly interact with ambient humidity and temperature. Slight absorption and release of moisture can modulate the release of hydrophilic aromatic compounds, contributing to the dynamic, living nature of the scent profile over time and in different environments.

- Moisture Regulation: While Hexiangzhu) should be protected from excessive moisture, the microporous structure allows for minimal and gradual exchange of water vapor. This can help prevent internal condensation or stress buildup during minor humidity fluctuations, contributing to the bead’s structural stability over time. A completely impermeable surface would be more prone to cracking under humidity stress cycles.

- Patina Development: Over years of handling and exposure, the pores interact with skin oils, atmospheric components, and the ongoing sublimation of aromatic compounds. This contributes to the development of a unique and prized surface patina – a subtle sheen and deepening of color that enhances the bead’s beauty and reflects its history. An artificial, non-porous surface won’t develop this authentic, lived-in character in the same way.

Pores as the Signature of Life and Craft

The “smiling” micropores on the surface of genuine Hexiangzhu) are far more than incidental features. They are the indelible signatures of a complex natural process: the escape of volatile life (aromatics, water, air) during the birth of the bead under the skilled hands of an artisan. Their presence, characterized by a naked-eye appearance of ordered clarity and a magnified view revealing natural subtle irregularities, is a direct consequence of the interaction between volatile organic compounds, natural binders, the physics of drying, and the irreplaceable human touch of hand-rolling and controlled curing.

These pores stand as a powerful bulwark against counterfeits, whose artificial surfaces – whether devoid of texture, crudely scratched, or bearing the sterile uniformity of molded “pores” – betray their lack of authenticity and the soul of true craftsmanship. Furthermore, they are functional, enabling the bead to “breathe,” releasing its precious fragrance slowly and continuously, interacting subtly with its environment, and developing a cherished patina over time. In the subtle landscape of the Hexiangzhu) surface, these microscopic portals tell a profound story of nature, art, authenticity, and the enduring allure of a living scent. To understand the pore is to understand the very essence of the genuine Hexiangzhu).